Because I'm reading way too much uninformed panic about the impact on encryption again: no, quantum computers are not the end of secure encryption, not even theoretically and even if they work perfectly.

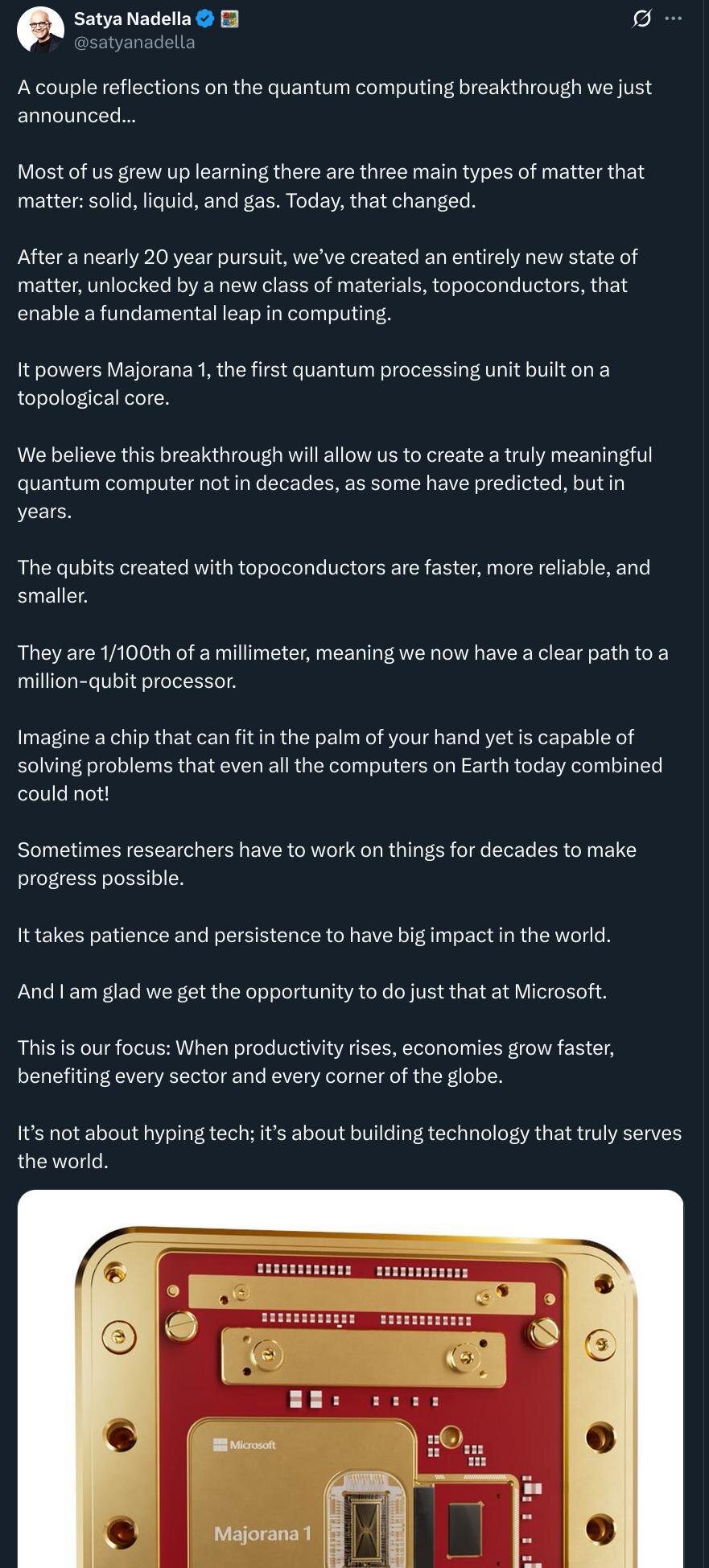

Context for this post: Microsoft's quantum computer announcement

The Relevant Quantum Algorithms

When considering this topic, two quantum algorithms are particularly relevant that we already know about, but can't practically use due to the lack of a working quantum computer:

- Shor's Algorithm

- Grover's Algorithm

1) Shor's Algorithm

This effectively solves the factorization problem of numbers. Relevant because the currently common asymmetric encryption methods (i.e., different keys for encryption and decryption) like RSA, DSA and ECDSA can be broken with it, as well as Diffie-Hellman key exchange.

2) Grover's Algorithm

Can effectively search in unordered data. This can be used to attack symmetric encryption methods like AES, BUT unlike Shor's algorithm, it's not a "magic bullet" here - it only accelerates the attack. Can be trivially solved with longer keys.

Post-Quantum Cryptography

The main problems that remain are:

- asymmetric encryption

- key exchange methods

For both, there are already known "post quantum" algorithms, meaning ones that cannot be attacked with Shor's algorithm.

Conveniently, they not only "fail" together but can also replace the same mathematical constructs. These are:

- lattice-based methods

- code-based methods

Why Aren't These Widely Used Yet?

Because they naturally also have disadvantages:

Lattice-based Methods

These are significantly slower in decryption compared to classical algorithms. This isn't too bad, since asymmetric methods are mostly only used to encrypt a symmetric key.

Code-based Methods

These have the disadvantage of requiring huge keys in the range of hundreds of KB. (For comparison: with RSA, 4096 bit keys are common, for example; 100KB would be almost 200 times larger). Annoying, but not a blocker on today's hardware.

The Most Important Reason

These methods are considerably younger and have seen little practical use, so they enjoy less trust than proven algorithms as long as there's no working quantum computer.

A premature switch risks overlooking problems and wastes the opportunity to further improve these algorithms before they become "cemented" through implementations.

Bonus: Would Bitcoin Be Affected?

Short answer: yes...

...but

Bitcoin uses two fundamentally vulnerable algorithms:

- ECDSA for signatures

- SHA256 for Proof-of-Work

The SHA256 for PoW is in my opinion completely uncritical if quantum computers become generally available - every miner can use them.

ECDSA, on the other hand, is toast with Shor's. But Bitcoin can already be used resiliently:

Shor's needs the public key to determine the private key. With Bitcoin using P2PKH, the public key is only revealed with the first payment from a wallet (before that, only a hash is known).

If a wallet address is only ever used once, the risk is largely minimized.

Nevertheless, Bitcoin should replace the signature method when working quantum computers are on the horizon. Fortunately, there are already concrete proposals, e.g., BIP-360: QuBit - Pay to Quantum Resistant Hash.

The Worst Case

This article examines the "worst case" - a well-functioning quantum computer that can execute Shor's and Grover's algorithms for large inputs without errors.

What Microsoft and others are specifically announcing is very, very likely more marketing hype than a real breakthrough that meets these requirements.

Conclusion

Quantum computers are a technological challenge for certain cryptographic methods, but by no means the end of encryption. The cryptography community has already developed solutions and is continuously working on their improvement. A rushed transition would be counterproductive - we have time to test and harden these new methods before practically usable quantum computers become reality.